Introduction

The Theban alphabet, sometimes called the Witches’ Alphabet, occupies a curious and enduring niche in the world of Western esotericism. Though not as ancient as Egyptian hieroglyphs or as complex as Hebrew or Greek, the Theban script has become a hallmark of occult writing, particularly among ceremonial magicians and Wiccan practitioners. Its appeal lies in its mystery: elegant, arcane characters that offer both secrecy and symbolism.

But where did this alphabet come from? And why does it continue to hold such significance in magical practice today?

Origins of the Theban Alphabet

Despite common assumptions, the Theban alphabet is not an ancient script. Its first known appearance is in Johannes Trithemius’ Polygraphia, published in 1518, a work dedicated to the art of secret writing and ciphers. In that text, Trithemius attributes the alphabet to Honorius of Thebes, a semi-legendary figure said to have authored The Sworn Book of Honorius, a foundational text in medieval magical literature.

However, no earlier evidence of the Theban script exists prior to Polygraphia, and scholars generally agree that Trithemius or a contemporary likely invented it, attributing it to Honorius to enhance its credibility. This practice of pseudepigraphy, attributing a text or artefact to a more ancient or authoritative figure, was not uncommon in early modern esoteric writing.

Nonetheless, the Theban alphabet gained traction, and was later reproduced in grimoires like The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) and eventually found its way into the magical revival movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Structure and Characteristics

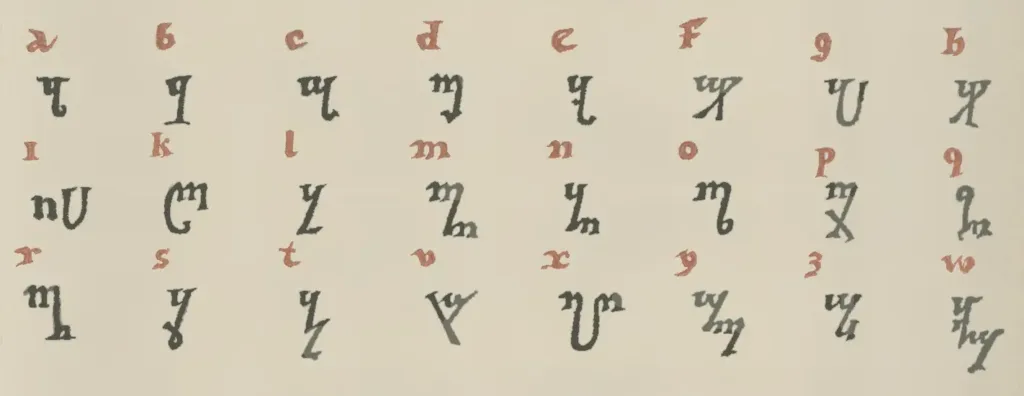

The Theban alphabet is a substitution cipher: each letter of the Latin alphabet corresponds to a unique symbol. It lacks its own punctuation and numbers, though practitioners often use Latin numerals or develop their own conventions when writing in Theban. Notably, the script includes no distinct characters for modern letters like “J” and “U” a reflection of the Latin alphabet’s historical forms.

Theban characters are typically written from left to right, and because the script has no grammatical function beyond encoding text, its primary purpose is symbolic rather than linguistic. It functions more as a sigil set than a true language, its power lies in concealment and consecration, not communication.

Use in Magical Practice

Over the centuries, the Theban alphabet has become closely associated with magical work. Practitioners use it to inscribe tools, label spellbooks (or Books of Shadows), write rituals, or create protective charms. Because it obscures the mundane content of a text, it adds a layer of secrecy, one of the classic hallmarks of magical operation. However, I’m sure Israel Regardie would thoroughly disapprove of this.

Why the Theban Alphabet Still Matters

In an age of unprecedented access to information, the Theban alphabet offers a curious kind of mystery: a cipher that is neither truly ancient nor especially secret, yet still rich in symbolic meaning. Its purpose isn’t so much to hide words as to honour them. Writing in Theban marks the text as something sacred, magical, or intentionally set apart from the everyday.

Final Thoughts

The Theban alphabet may not have roots in the temples of ancient Egypt or the libraries of Babylon, but its mystique endures. Its looping, sigil-like forms appeal to the modern imagination while preserving a connection to a lineage of magical secrecy. Whether you’re inscribing a candle, crafting a talisman, or keeping your personal grimoire from prying eyes, the Theban script offers a symbolic veil, a threshold through which intention becomes form.

And in the end, perhaps that’s its truest magic: not in its origins, but in the purpose it continues to serve.